Entertain me for a moment while I present a conspiracy theory. Congress banned multi-member House districts in 1967 in order to curb the threat of proportional representation.

John Patty over at Mischiefs of Faction reminds us that, if your subjective sense of gerrymandering offends you, you should support statewide, multi-member elections to the House of Representatives. He alludes to “other problems” that occur when multi-member elections are done by plurality rules. The main problem is that a single slate of politicians can win every seat.

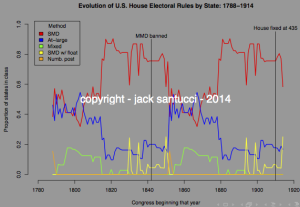

Now, Congress first mandated single-seat districts in 1842, but plenty of states flouted that law, as you see below. The graph overstates the flouting somewhat, since it classifies states according to their formal rules (i.e., if you have “at-large” elections but only one seat in the House, you’re technically using a single-seat district). It also overstates the flouting because some states dragged their heels in redrawing maps when apportionment granted them new seats. But the overstatement isn’t a total one; some states definitely flouted the multi-member district (MMD) ban well into the twentieth century.

So there are two puzzles. First, why did Congress reopen the issue again in 1967? Second, why did states actually comply with the MMD ban this time around? The answer to both may be: fear that proportional representation (PR) could become reality. Allow me to explain.

First off, PR was on the agenda well into the 1950s and, in some places, early 1960s. Its advocates had real, working examples to point to in some large American cities.

Now, consider that Congress passes its latest MMD ban in 1967. Historically-minded readers will note that 1967 follows a string of civil and voting rights legislation and litigation. We need not review all of it here. Just focus on a few key items.

Three cases from 1962-1964 make redistricting a justiciable question, and they establish the “one-person-one-vote” (i.e., no malapportionment) rule. Just as jurisdiction-wide MMD preclude gerrymandering, so do they preclude malapportionment. In other words, these cases opened the door to court-sanctioned, at-large districting.

Turning to legislation, we then have the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA). Section 2 banned election arrangements that discriminate on the bases of race, color, and/or language. Section 5 said certain jurisdictions have to ask for permission when they tinker with election arrangements, and section 4(b) established which jurisdictions those are. They were not just in the South. And some of them (e.g., New York City area) had used PR before.

So the Warren court malapportionment decisions open the door to MMD, but the VRA raises questions about minority representation if those MMD come with plurality rules. The obvious solution to anyone who’s ever taken a comparative politics class: replace plurality with proportional representation. That solution might also have been obvious in Hawaii and New Mexico, the only two states still using at-large elections, both of which were then covered jurisdictions. And it might have been obvious in the host of states with racially gerrymandered and/or malapportioned, single-member districts. It was definitely obvious in the Queen City of the West when, in 1957, the forces of repeal stoked fear that PR might yield a “Negro mayor.”

Lo and behold, in 1967, Congress passes the Uniform Congressional District Act, the latest ban on multi-member districting. No state adopts PR. No state retains MMD plurality. No state flouts the law by adopting MMD plurality. Everybody complies.

Twenty-six years later (or thirteen terms in the House if you prefer to measure it that way), Clinton’s nominee for Assistant Attorney General says nice things about PR, which kills, in part, her nomination.

If you think that first-past-the-post is baked into the Constitution, you’re probably not reading this blog. If you think that the United States chose their electoral rules in 1842, you’re right; they did whatever they wanted. But the United States really chose their electoral rules in 1967.