I just finished teaching/discussing a classic article on NYC party politics in the 1920s-50s. It was an interesting coincidence that the Working Families Party had just done well the day before in some Northeastern cities. (The Libertarians also did well, but that is a potential connection for later.)

Shefter’s piece is not easy to read. It was one of the first to run in Studies in American Political Development. The theory casts “political incorporation” and “extrusion” as “two sides of the same coin” of the handling of “new social forces” in American politics. All these terms need interpreting.

The argument also rests on details about many forgotten local politicians. That is a lot to keep track of. It also mentions interest groups, both formal (like the Citizens Union) and informal (like the mafia).

I taught the piece with pictures of the underlying coalition structure, light discussion of the electoral institutions, and a bit on the then-emerging New Deal party system. (The other key part of the theory is a “crisis” or “realignment” in/of the party system.) Then we interpreted the key terms. Then I had students look up names from the article (La Guardia, Marcantonio, O’Dwyer, Powell, etc) and try to say how their portrayals supported the theory.

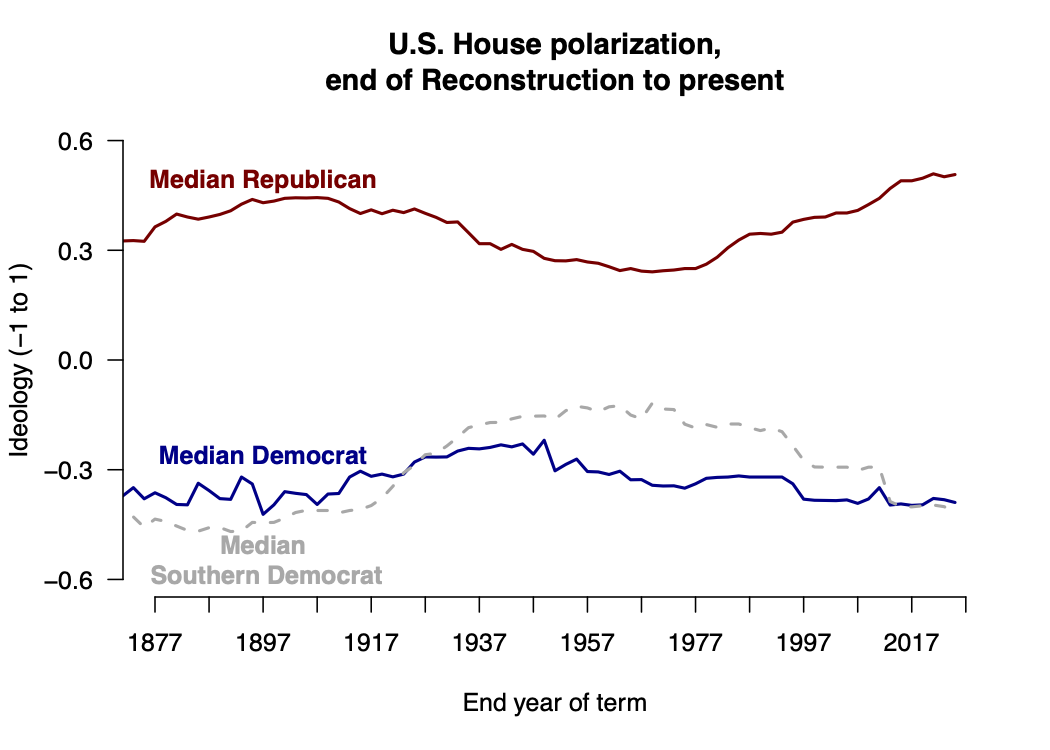

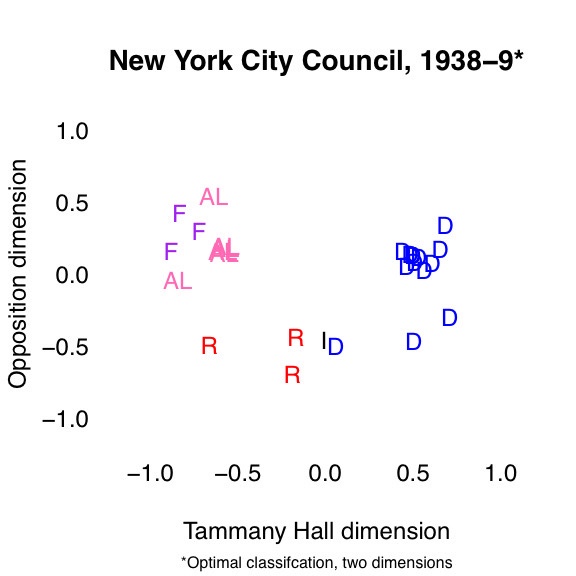

Here is the initial post-reform coalition structure. By reform I mean the institutional changes of 1936.

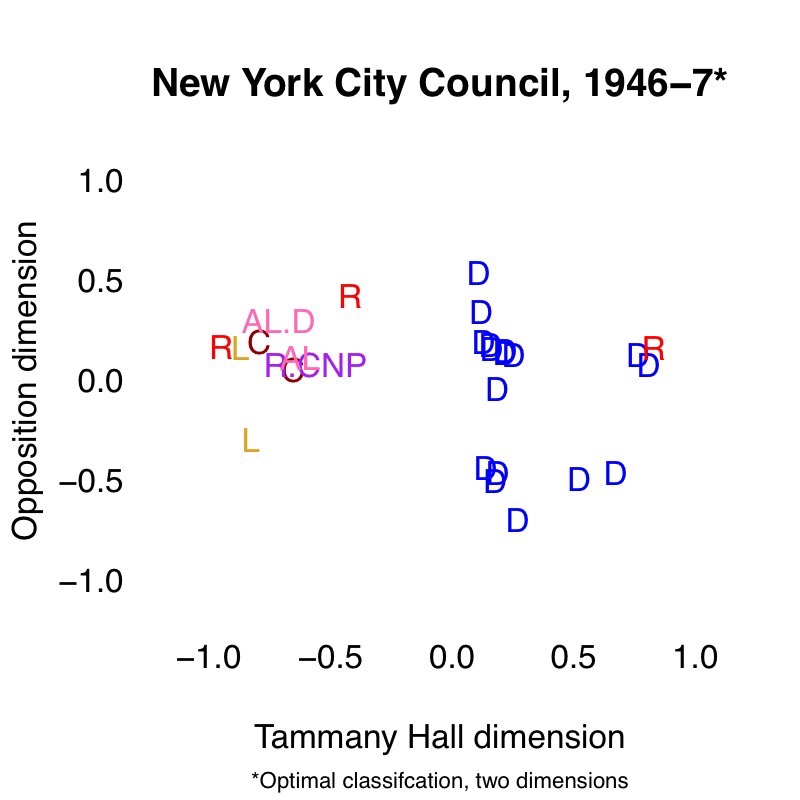

Here is the coalition structure as the institutions were about to change again.

There are clear differences, and these mapped nicely onto details in the article.

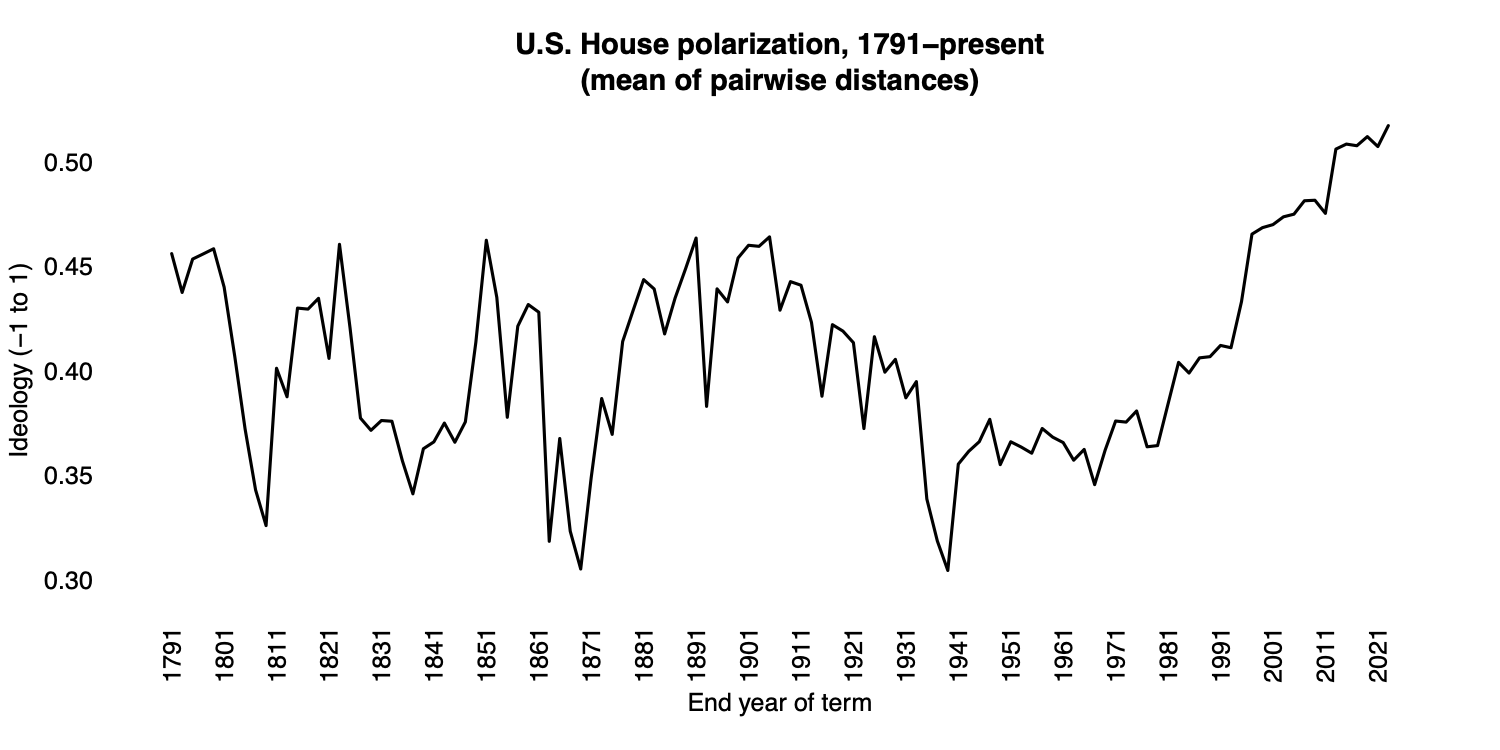

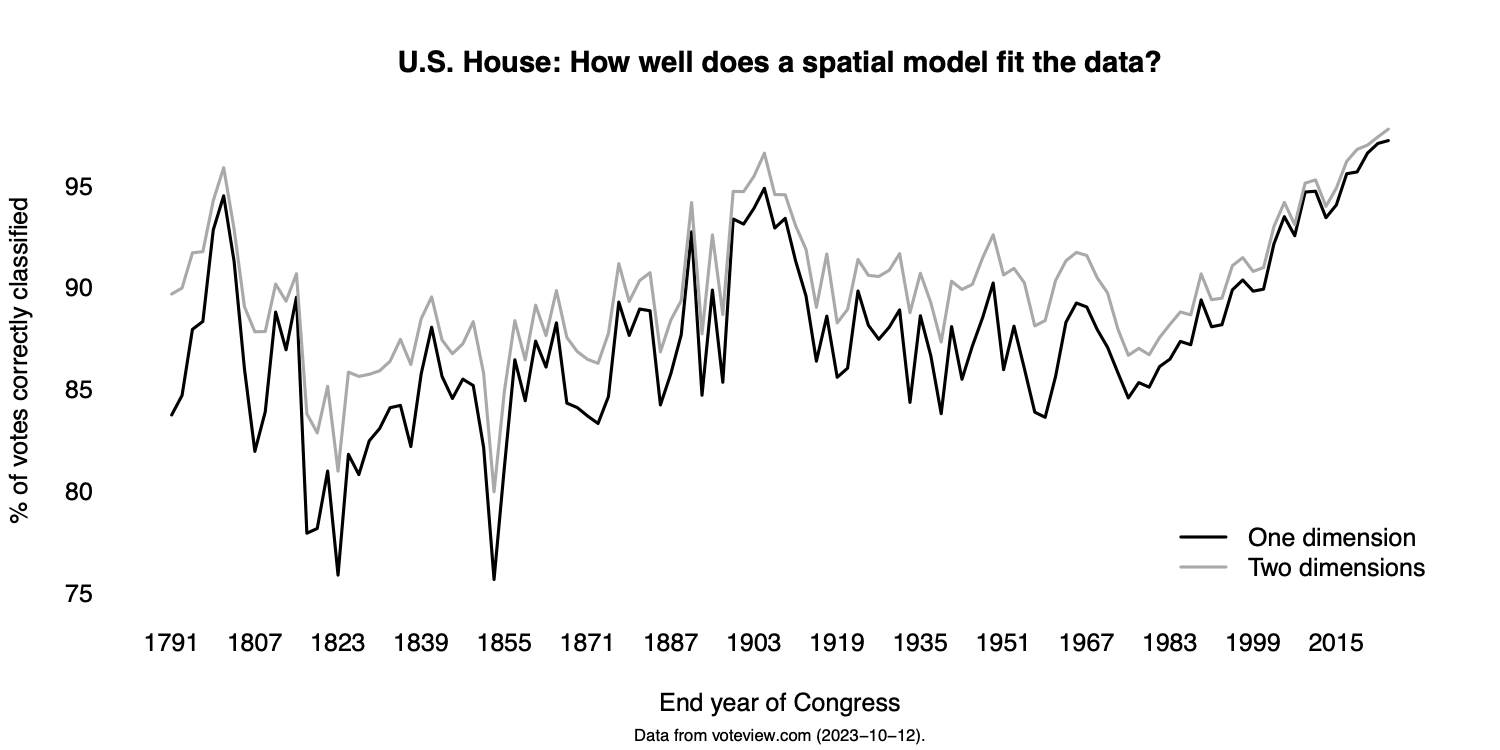

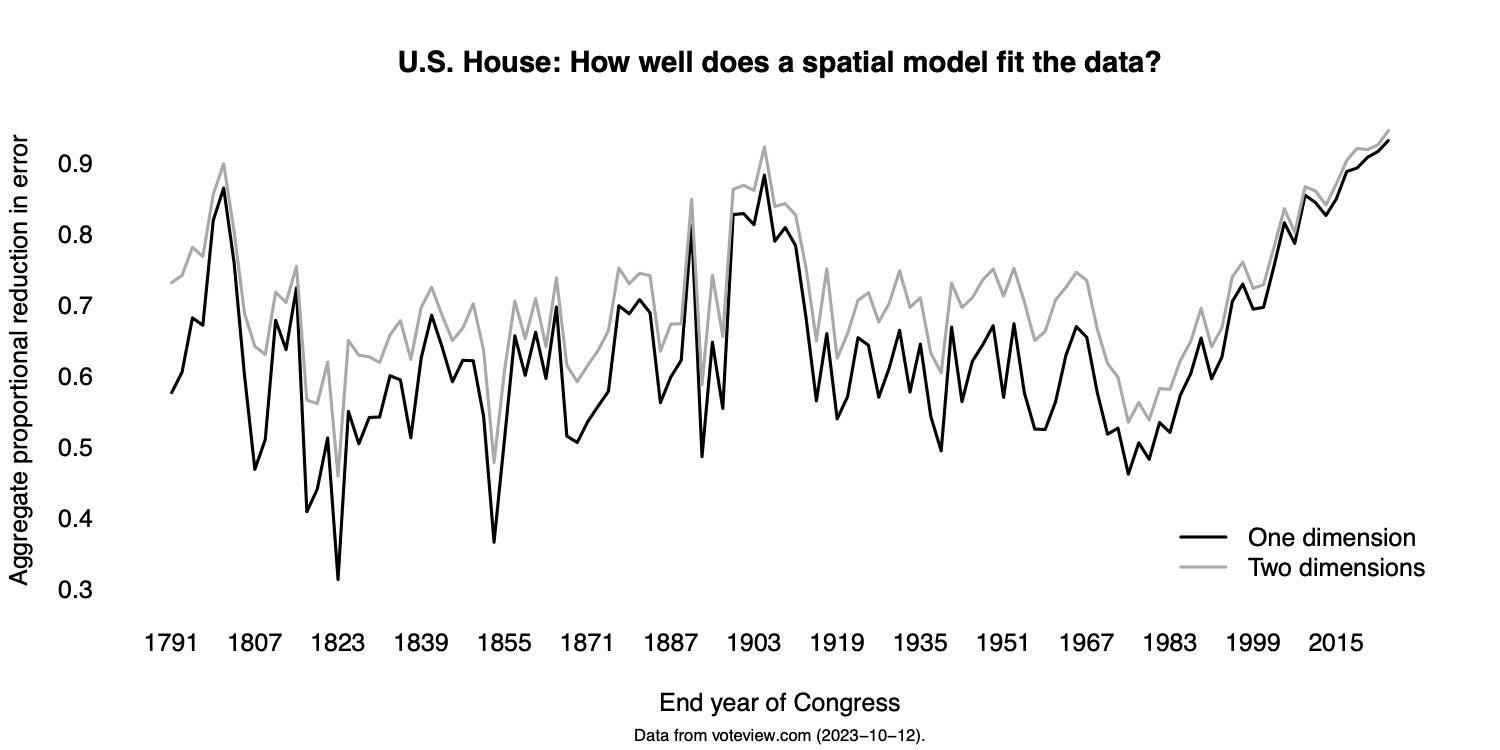

The images are illustrative, not authoritative. I made them several years ago. The newer representation of these data was done instead by scaling everything together (due to the attendant research purpose).

I did not bring up the WFP at all. One student did mention AOC, and we discussed how well the framework fits her trajectory, which historical figure seems most similar, etc.

I have been thinking a lot about how all of the above relates to nationalization, as well as another book I look forward to reading on that.