People on both sides of politics agree on the need for some kind of electoral reform. “The current system isn’t working,” we hear often.

Yet the reformers on each side face a different set of problems. This leads to diverging institutional preferences: in terms of seats/votes proportionality and expected effects on party discipline. The result will be no reform at all, state/local efforts to promote “proportional ranked-choice voting,” or a set of compromises (policy- and office-seeking) that neither side seems willing to make.

The Democrats’ problems

Democrats face two related problems. One is insufficient party discipline. Witness the failure last December to shepherd voting-rights legislation through the Congress. Or the scuttling of Joe Biden’s Build Back Better legislation.

A second problem, well-documented by Rodden and the gerrymandering crew, is the concentration of their voters in population-dense regions. This is why we hear that Democrats are disadvantaged, relative to Republicans, when it comes to translating votes into proportional (or better) shares of seats.

These problems are related because, to win congressional majorities, Democrats must appeal to voters in conservative areas. Hence the production of a caucus whose own members defeat its priorities.

If I have captured the problems accurately, the institutional prescription is straightforward. Find a reform that undoes the geography problem, then makes individual members more beholden to party leadership: list PR.

The Republicans’ problem

Republicans’ problem is much different. The NeverTrump wing of the party has a #PrimaryProblem. Solving the #PrimaryProblem requires replicating the Murkowski coalition. In turn, that requires permitting two Republican parties to present themselves on one ballot, then getting a sufficiently large group of Democrats to cross over.

The reform solution is accordingly different: preserve single-seat districts, and break the major parties into factions.

Prospects for reform

If I have characterized the situation accurately, there is little hope for a congressionally imposed solution. Democrats need proportionality and more leadership control of nominations. Republicans need disproportionality (i.e., the district-structure status quo) and less leadership control of nominations. Democrats from conservative districts may face similar incentives.

What about how the expected number of parties affects reform prospects? Some Democrats likely do not want the party’s left wing to bolt. Republicans likely do not want a governing coalition to include that party. Hence some opposition to PR in both camps. And others may be steeped in the idea that multiple parties equal instability.

For various reasons, I don’t think the bolt is likely. Even if it happened, it might not matter — if reform made parties stronger, leading to the style of coalition politics that we find in most other democracies.

Further implications

Very few observers are making any sort of case for list PR. One possible reason is precisely that list PR implies greater leadership control of nominations.

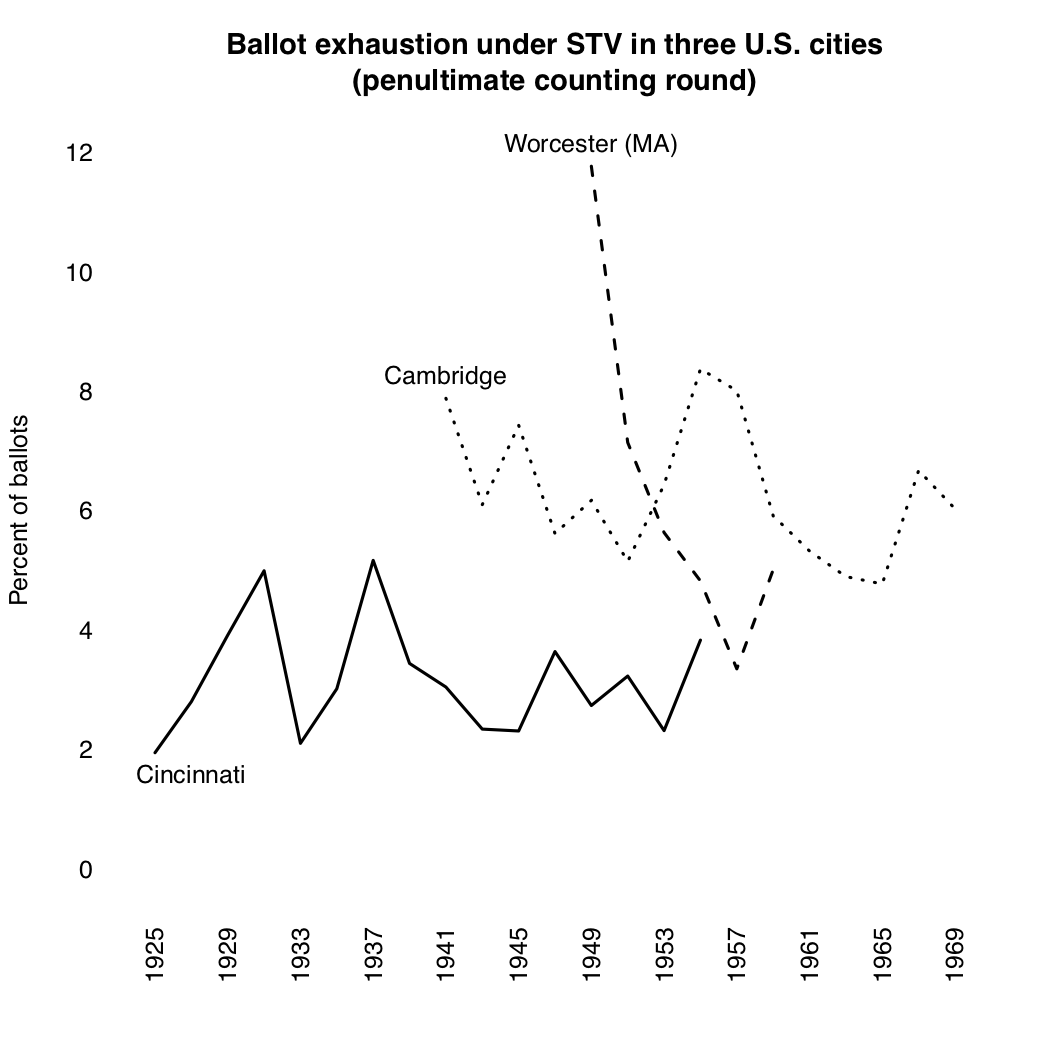

Further, list PR does not ‘work’ with a system of nonpartisan elections. Only the single transferable vote (STV) can show progress if the goal is to create “demonstration cases.” Given the analysis of congressional prospects above, demonstration cases may be the best a reformer can do.

Is there a way out?

No, probably not without some policy concessions.

For Democrats, the Republican reforms mean leaving Republicans in control of the House. For Republicans, the Democratic reforms mean splitting the GOP in two — full-blown parties, not factions, to regulate the party lists — as well as ceding House control for the foreseeable future. It also might mean giving up the White House, unless the two Republican parties fused to contest those races.

Should there be a way out?

Yes, I think we are at a pivotal moment. I think our grandkids will speak poorly of us for failing (a second time) on voting rights, then leaning into ‘incremental’ reforms with an iffy track record.