“Downward cascade” refers to a potential one-person-one-vote violation in the block-preferential form of ranked-choice voting (BPV). Ben Reilly introduced me to the term when we wrote this piece on BPV.

BPV aims to find the majority winner for each seat in a multi-seat district. It does so by breaking the election into “tabulations” — one for each seat. All votes from tabulation t proceed to t+1 and so on. The key word there is “all.” The winner of the first tabulation does not proceed to the second, but the votes that elected that person do.

So we say that votes can “cascade downward” from the first winner to others. This is not the same as a “transfer” in any of the other transferable-vote systems. Those transfers aim (in theory) to give each vote equal weight.

KPCW radio has a story on the outcome. Here is the key bit:

Candidate Christen Thompson ranked second in the race for each of the three city council seats, so he was not elected. While he said he’s disappointed, he still supports the ranked-choice system.

“I really like ranked choice, because it really gives people the chance to vote for what they believe in… without being afraid of losing their vote,” he said.

The city website lets us verify the district magnitude.

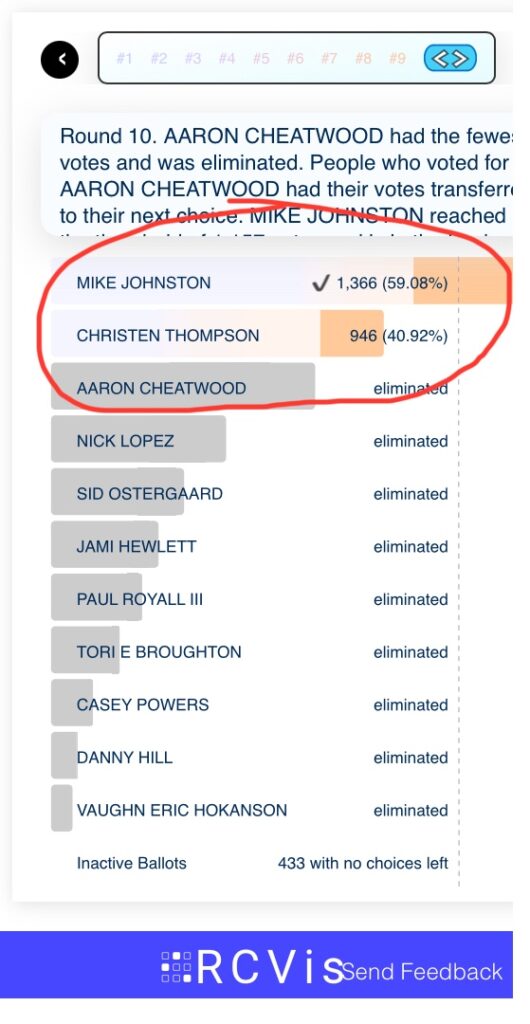

It also lets us see a BPV count in action. Pay attention to the final-round count in each tabulation. (It may help to follow the fate of Thompson above.)

The data suggest that downward cascade from Johnston and/or Cheatwood helped Ostergaard beat Thompson. Ostergaard was in fifth place at the end of the first tabulation.

Had the city used the “bottoms up” form instead (again see), the top three candidates from the first tabulation would have won the seats.

Alas, “bottoms up” is not popular with those who insist on theoretically majoritarian reforms. Nor is single transferable vote, since it is widely seen as (semi-)proportional.

Australian Senate elections were by BPV for three decades.