Two motives currently define demand for a system of proportional representation (PR). One is to increase the number of parties. Another is to bring parties’ seat shares closer to their vote shares, regardless of how many parties there are.

Two motives accordingly define opposition to PR. One invokes governability issues from an increased number of parties. The other, which we do not hear in public, is that PR would benefit the party (coalition) whose voters concentrate in population-dense areas.

So, one flavor of opposition and one flavor of support share a premise that PR increases the number of parties. This short post aims to share some data on the validity of the premise. What I take from these data is in line with something I wrote last summer: “the current conversation is too focused on the number of parties.” By that I meant both opposition to and advocacy of PR.

Below are some data from Calvo (2009). (I would include the link if I could find it.) That paper argued that districting considerations — not a desire to improve representation — are fundamentally responsible for PR adoption in Western Europe.

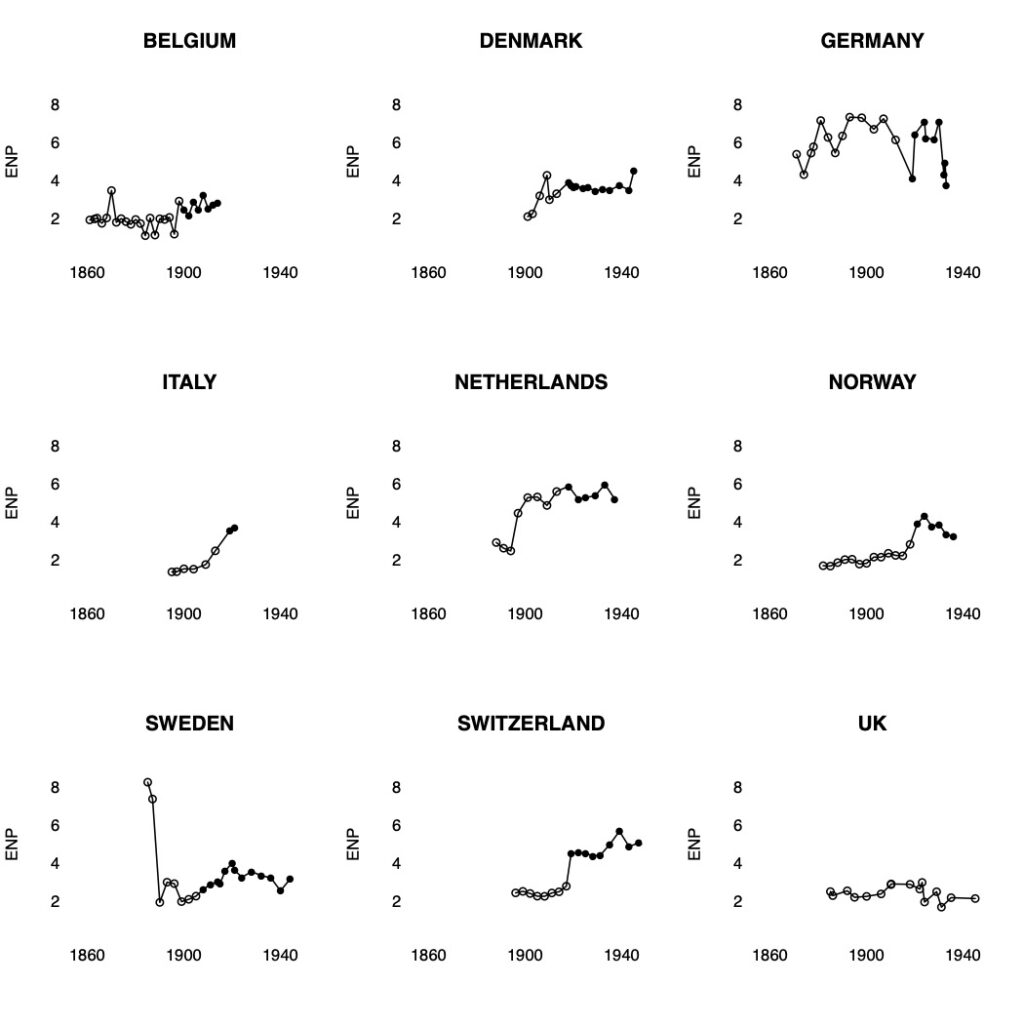

Our first set of graphs focuses on the “effective number of [electoral] parties” (ENP) in lower chambers. In these graphs, an empty data point is an election without PR, and a filled data point represents an election under PR. As a benchmark, ENP in United States House elections typically is within 0.1 of 2.0. ENP tells us what voters are doing, possibly but not necessarily in response to PR adoption.

The graphs above show increases in the number of parties in advance of PR adoption— but not mechanically and not in all cases! Also, only one case shows a proper post-PR ‘jump’ in the effective number of electoral parties: Switzerland. I argue elsewhere that this is because the Swiss PR adoption was a ‘realigning’ episode, made possible by prior adoption of nationwide initiative-and-referendum. Lutz (2004) thus calls the Swiss PR adoption “reform from below.”

Bottom line: the number of parties may have mattered but not in the way some argue: things ‘pressing’ for and being given representation. Rather, and channeling Calvo (2009), multiparty politics made it so that majoritarian electoral rules could no longer be relied on to deliver majoritarian outcomes. Here is a stylized story for any of the above plots except Switzerland (again, reform “from below”). Dealignment, possibly due to an influx of new voters, begins putting pressure on incumbent party leaders and legislators. They debate what to do for a while. Then they conclude that the best way to hang onto power might be to adopt PR.

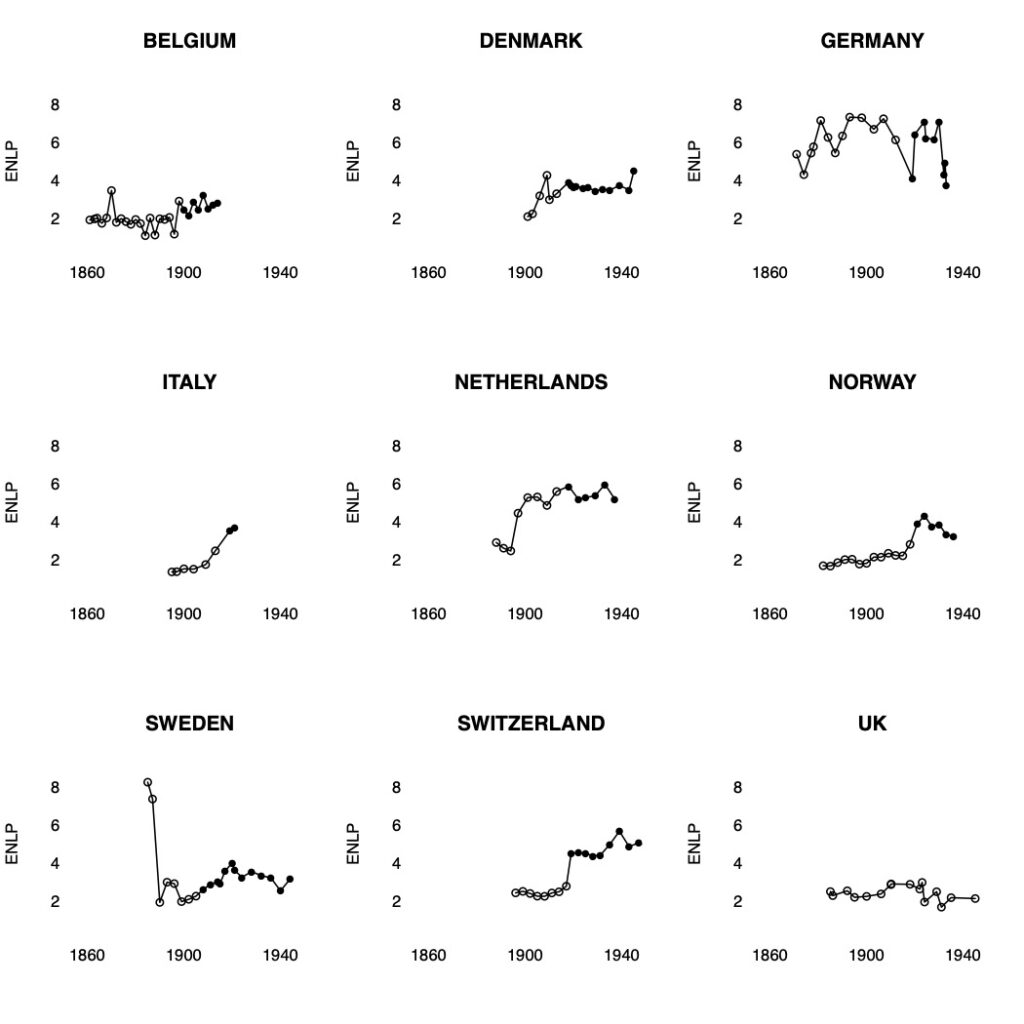

Here are data on the “effective number of legislative parties” (ENLP), or the size-adjusted number of parties actually in the legislature. They do not look very different from the data on ENEP.

Both measures suggest that PR does not much affect voting behavior, at least in the short term. In turn, this suggests that PR probably does not do much to harm governability. Rather, in a world where governability matters, PR adoption more likely stems from a desire to preserve “governability” — by the coalition adopting it!

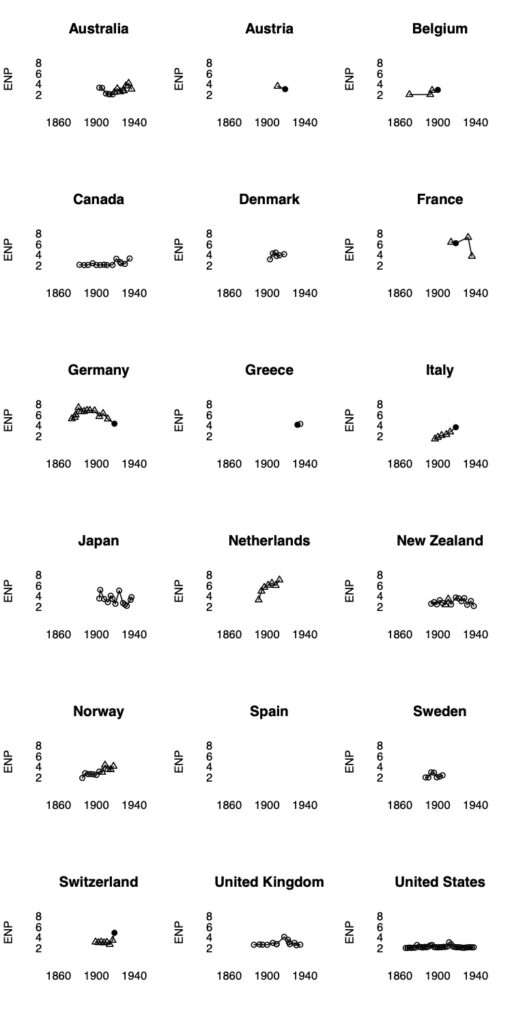

Below is one more look at ENP, this time with data from Blais, Dobrzynska, and Indridason (2005). This look includes the Anglo settler democracies, which many readers will want to see. Here, a filled dot represents the first election under PR. An empty dot represents an election under plurality, and an empty triangle represents an election under strictly majoritarian rules (runoff, Alternative Vote). The key thing to note, especially for the Anglo democracies, is that an increase in the number of parties does not mechanically cause PR adoption. Other things are going on.

We are at a point when many people like the idea of PR. More precisely, many have become comfortable with, if not supportive of, an increased number of parties in the United States. (That is a sea change from when I entered this research area.) I agree that under certain circumstances, multiparty politics with PR is a good idea. My point is that the number of parties gets more attention than it should — as a threat to governability, as a ‘stepping stone’ to PR, and maybe as an end in itself.

What matters more than the number of parties is that majority coalitions, be they single-party or alliances of parties, can win majorities of legislative seats and then hold themselves together between elections. (I am nearly plagiarizing myself, except that I am citing myself.) If those ideas sound good, you want two things: a system of proportional representation, then one in which a party’s leaders have the tools to discipline their rank-and-file.