This post is on the connection between oversized majorities and waves of political reform. Here I am thinking about ranked-choice voting in historical context, though one might say the same about direct primaries. I think reforms like this take off when:

1) Most people lean to one side of the ideological spectrum;

2) But that side of the spectrum has serious, internal cleavages.

The basic idea is that the logic of minimum-winning coalition is not holding in some way. The political majority is oversized, so much of the action is inside it. That fighting finds expression first as party splits, then as reforms to foster coordination. I have floated this hypothesis before. Others are starting to touch on it. Let’s look at some data.

A new brief from Brookings makes three relevant points. First, young voters are leaving the party system at an increasing rate. Although they may vote for Democrats or Republicans, they do not want to claim those labels for themselves. These trends are hurting the GOP more than they hurt Democrats. And we can find these trends in state politics as well.

Another big news item is the collective rediscovery of electoral reforms — particularly those that accommodate multi-party politics and/or independent runs. Larry Diamond says it well:

We are entering a new era of political reform in the United States, driven, like the last big one of a century ago, from the bottom up. And the voters of Maine have just given this movement its most courageous and inspiring victory.

The last big reform wave was, of course, in the Progressive Era. What’s theoretically interesting is this. During that period, the Republican Party had a natural supermajority. As such, most of what was interesting in politics was happening inside that tent (e.g., labor unions and captains of industry in the same coalition). Since the fighting was within the Republican Party, that party had to become the party of reform.

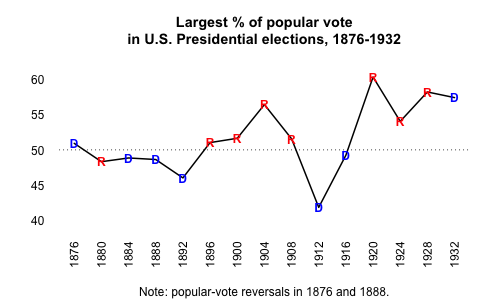

Here is a picture of that fractious, Progressive-Era supermajority. Most would date the system in question to 1896. It ends in 1932, when FDR rescues the Democratic Party from its status as a regional one, dedicated to voting restriction. What we see in 1896 is the start of a trend away from Gilded-Age, 50-50 competition. In 1912, we see the damage done by Teddy Roosevelt. But the coalition repairs itself, at least at the national level, winning huge majorities through 1928.

The party split in 1912 basically fanned some reform flames that had burned in state and local government since the early 1900s. I note this in my web piece on Maine’s RCV vote last week.

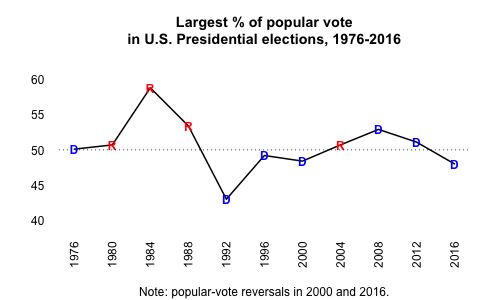

A century later, the parties’ roles may be reversing. Now the Democrats may be turning into a supermajority party, complete with a shaky reputation among younger voters. This would explain why RCV has tended to find favor in liberal cities. (The same logic holds in more conservative states of the Southwest, however, where Republicans have held oversized majorities.)

We need to watch for two things going forward. First, will the Republican Party recover? Some insist it will. Second, how will Democratic leaders handle pressures inside their coalition?

Or maybe I am reading too much into all of this. Here is the vote-plurality trend for presidential elections in the Sixth Party System. Once we get through 2020, we will have a better handle on the future.