It has been two years since I finished/sent in More Parties or No Parties. Three issues with the theory have been on my mind. To recap, the theory says that “reform is common in periods of realignment” (or something along those lines). Then it says that a reform episode can be any of three types: insulating (comes from incumbent coalition), realigning (out-of-power folks peel off portion of incumbent coalition), and polarizing (opposing sides collude). The types were strictly internal to the polities whose institutions they were changing (cities for me, countries and some states for the lit review).

I do not have a thesis statement. I am making a list and riffing on it.

The first issue concerns coalition shift in general. I had cast this as resulting from activation of a coalition’s internal disagreement(s). Might not the addition of new players also destabilize a party system? (I think I acknowledged this possibility in a footnote.) Or might not the emergence of new issues do the same? I am thinking here of climate change especially, which is a ‘shock’ par excellence. It also has all sorts of implications for the issues that otherwise define the ‘basic space’ of a party system. What do we do when the ocean swallows the Outer Banks of North Carolina? Move the rich? Move everybody?

Another issue concerns the trigger(s) of a ‘realigning’ reform episode. Does the reform cause realignment, or does realignment cause the reform? The book argues that realignments cause reform, but a ‘realigning’ reform brings about (facilitates) realignment. So, which comes first? I suggested in ch. 8 that coalition shift at a higher level of government might produce demand for a realigning episode at some lower level. That would help to integrate other accounts of the reform adoptions I studied. For example, one good BA thesis argued that the Worcester reform charter was a business-community reaction to the rising power of the Irish — an insulating episode in my typology. I suggest it’s not this simple; the reform coalition included many people (Democrats) who helped elect a Mayor on the same day they ratified a charter meant to destroy his party. The key questions for me are about the magnitude and rapidity of change in advance of the reform. How big had the local Democratic Party gotten, and why? Maybe it comes down to an expanding set of salient issues, regardless of whether that’s at a higher level of government. I did find suggestive evidence with respect to unions. Maybe these are the same thing, at least sometimes.

Hopkins’ (2018) theory of nationalization is something I wish I’d brought in. Nationalization (as I integrate it into my mental model) means that higher-level cleavages are reshaping lower-level party systems. Or, in terms that are closer to those of Hopkins, national-level issues are more salient (for most people) to local politics than local-level issues. This leads (in my mind) to ‘oversized’ parties in some places, so that basic economic issues get debated within the oversized party. Witness non/bipartisan claims about corruption and how to pave a street.

Moving on.

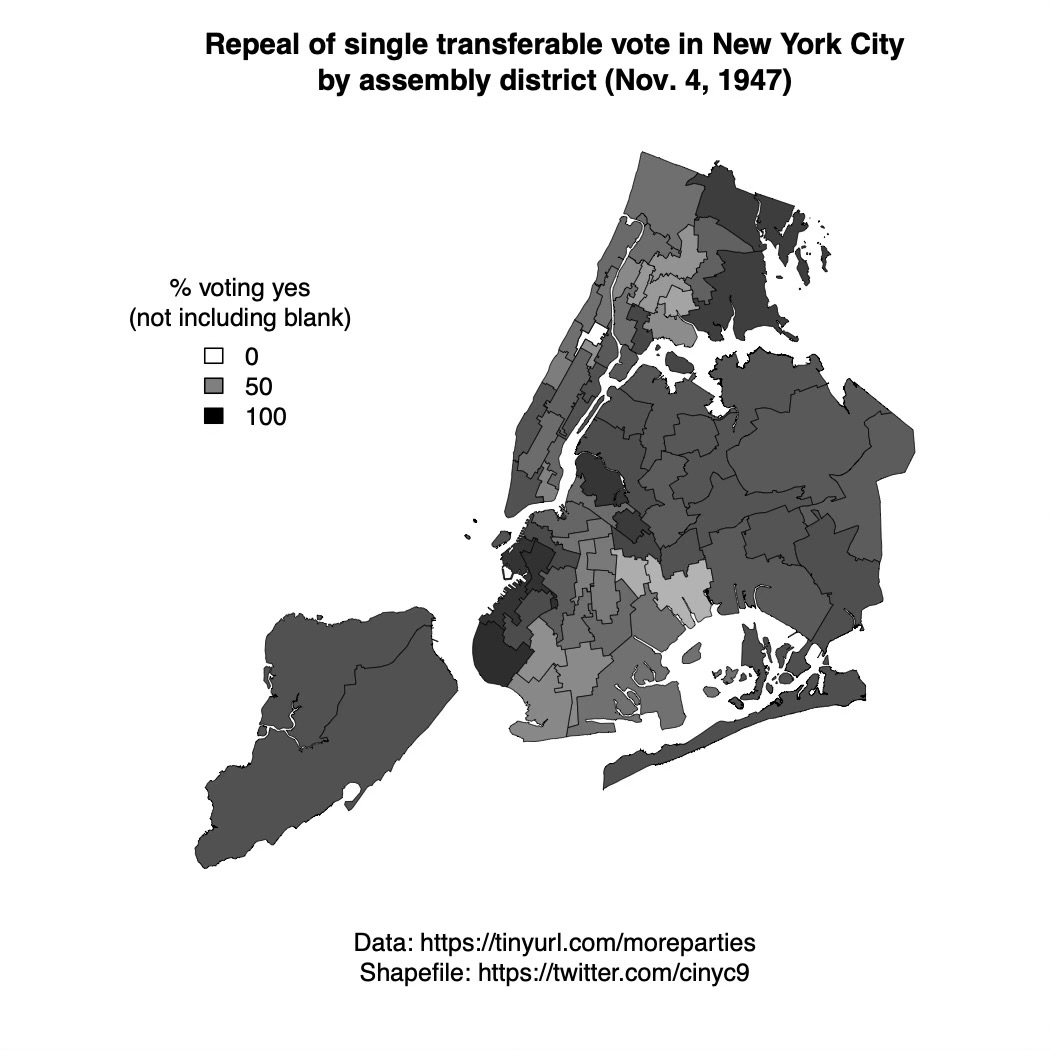

I’m also not thrilled with having cast New York City (1936) as a ‘realigning’ episode. I am not saying this was wrong. The complication was the local separation-of-powers system. At the time of the reforms, Tammany controlled the Board of Aldermen, but LaGuardia controlled the mayoralty. And LaGuardia had won (and presumably controlled) a citywide vote majority.

So, maybe, the NYC reform was about creating congruence of control between the branches of government. (What the NYC reform package did to legislative power is fascinating, but let’s save it for another day.) Here is the article one might cite, then the key line: “Politicians became advocates of direct democracy, we argue, only where they were confident that voters were likely to agree with them and where current institutional arrangements blocked the median voter’s influence” (emphasis mine). Another way to put that: existing institutions (like malapportionment) were stopping statewide majorities from translating that strength into seat shares. That article is about different reforms, but the theory seems helpful. I also wonder if the identity/priorities of the ‘median voter’ changed in the period under our shared consideration (1898-1918). Otherwise, how would it have been possible to get around the incumbent coalition?