There has been a boom of late in estimating the policy effects of historic local-government reforms. Those were often tied to forms of preferential voting. I want to share what I found when I did my own study of spending effects.

The takeaway is: higher aggregate spending under a council-manager charter that included single transferable vote (STV), compared to cities with non-STV manager charters, as well as cities whose ‘form’ of government didn’t change. I argue that this is to be expected, based on how the STV-manager charter combined the logics of “neighborhood representation” and “citywide focus” (both of which are common phrases in reform-practice circles).

The variety of reforms

Progressive Era municipal reforms came in three main flavors. One class strengthened directly elected mayors relative to local assemblies. It is not common to call this a “reform charter.”

Two more inaugurated the infamous ‘at large’ election. (On infamy, see Trebbi et al. 2008 or this new paper by Grumbach et al. 2023.) These also seem to have reduced the sizes of local assemblies.

One of them, the commission form of government, attempted to hold citywide elections to a series of functionally defined offices. Over time and to varying degrees, this morphed into a ‘numbered post’ electoral system. My former research assistant Andrew Rosenthal and I found nearly 100 such cases that came with an early form of ‘instant runoff.’ It is clear from historic advocacy materials that popular interests in preferential voting and more businesslike administration reinforced each other in helping commission government to spread.

The second at-large charter was designed, in part, to be compatible with some form of proportional representation (PR). It also aimed to piggyback on the joint popularity of preferential voting and businesslike administration. This was the council-manager form of government. It achieved compatibility with PR by junking the numbered posts.

Recent research

Two recent papers supply the impetus for this post. One from Carreri et al. (2023) finds limited effects on a range of inequality measures (pp. 13-14) from at-large-charter adoption, 1900-40. Another from Sahn (2023) disaggregates the two reform charters and points to greater capital outlays, 1900-34, from council-manger adoption. This is important; recall the “citywide focus” that council-manager is said to promote. (Also see Hankinson & Magazinnik 2023 on housing policy under at-large elections.)

There probably are other recent papers. I do not follow the historic urban political economy literature as closely as I might. I got to the topic by trying to say something about the effects of the reform I was studying (STV as embedded in a municipal reform charter).

Party competition in nonpartisan elections

My analysis used the data from this paper and focused on the period from 1930-60. This is important because, in 1932, the National Municipal League (NML) formalized the following policy: urge local reformers to form a “good government” party in any city where NML also was promoting council-manager. So, when we estimate the spending effects of these institutions, we may be picking up effects of the styles of party coordination they engendered.

It is worth noting that the new STV-manager charter in Portland (OR) once again has local reformers figuring out how to organize slates.

I argued that STV’s collision with a reform charter should lead to higher per-capita spending than non-STV charters and the absence of reform. The reason is that STV turned “good government” slates into “parties of neighborhoods.” The openness of an STV election made it unwise for reformers (now seeking to control government) to ignore (or harm) any given neighborhood. Evidence that politicians were thinking along these lines appears in the chapter. It includes first-choice vote shares by ward (when available), stories about campaign strategy, and stories about legislation (spot zoning, holding up slum clearance, etc). There also is a comparative literature on “localism” in STV elections (see, e.g., Carty 1981 on Ireland).

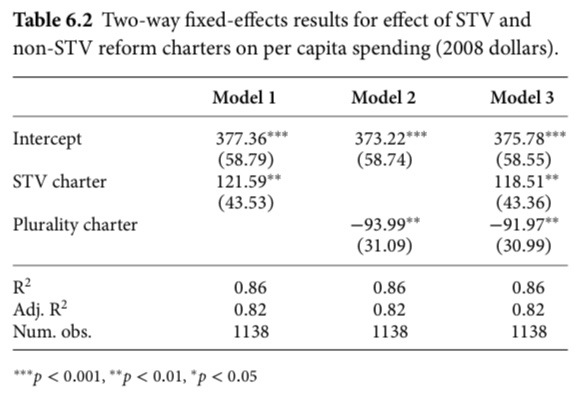

Here is the key table. “Plurality charter” really means “non-STV manager charter.” Unreformed city is the reference category. What this means is that the data do not record a change in form-of-government.

What we see above may combine what I’ve said about STV, plus the capital-outlays finding from Sahn.

The data in the other papers is better than what I used. Diff-in-diff also went into convulsion as I was writing my chapter, so I fell back on two-way fixed effects. I also did an RDD with pre-1930 data at one point, and that turned up no effects.