I spent a chunk of Memorial Day weekend writing up some thoughts on fusion. They apparently are part of this case (which does not affect my views). Here is the opening paragraph:

I have been asked to share some thoughts on political parties, democratic stability, and the relationship of each to ballot fusion (understood here to mean cross-endorsement). What follows is based on my doctoral education and ongoing research into so-called ‘multiparty reforms.’ A key theme will be that the number of parties matters less than whether the electoral rules facilitate coalition, then make such coalitions unambiguously known to voters. Cross-endorsement fusion has desirable properties on both fronts: promoting coalition, then telling voters on the ballot what coalition they aim to place in control of government.

The ideas in the ‘expert report’ are based partly on material from an early draft of my book, but which I decided to save for stand-alone publication.

That part of the book deals with “making reform work,” especially against the joint backdrop of presidentialism and the Electoral College. I might as well share the language now.

No consideration of multiparty American democracy is complete without attention to the presidential system of government. There are two big problems: the Electoral College unit rule, then the so-called separation of powers. I will suggest ballot fusion as a way to deal with both. The reason is that it promotes more efficient bargaining than the leading alternatives, namely, ranked-choice voting and runoffs.

In the American system of presidential elections, a third-party candidacy poses two big threats. One is that the trailing candidate may win the election — not only because the system advantages low-population states, but also due to spoilers in electorally pivotal states. Another is that there may not be a majority in the Electoral College, throwing the decision to the House of Representatives (where each state delegation votes in block). The strongest institutional explanation for our two-party system is the “unit rule” allocation of a state’s electors to the popular-vote winner in said state. This system solidified in 1836, not accidentally alongside the two-party system itself (E. J. Engstrom 2004). Had we become democratic in the era of multiparty democracy, it is likely we would use some other method to elect the President. Clearly, if we are to have majority rule and multiparty government, there needs to be some new mechanism for presidential elections.

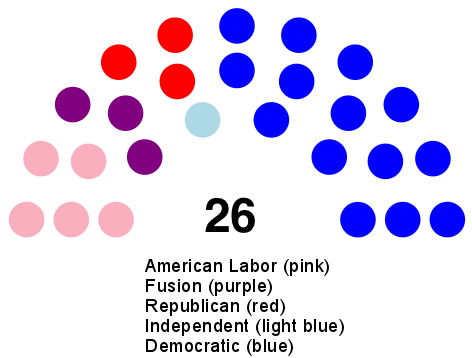

With either problem, the issue is to promote bargaining, leading to some coalition with majority support. One possible option is electoral fusion. Under fusion, two or more parties nominate a single candidate, and voters may support that candidate on as many ballot lines as there are nominating parties.

Fusion is not the same cross-filing, which allows the candidate to choose which party labels appear near their name (Masket 2009) […]

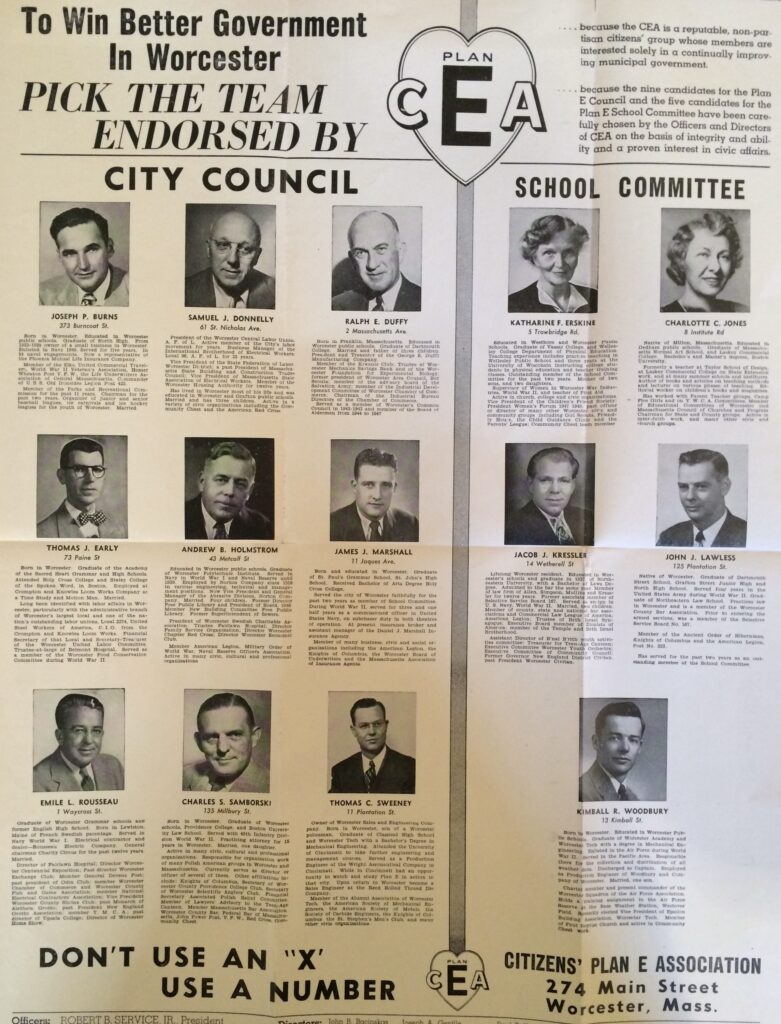

Fans of other systems (e.g., runoffs, single-seat RCV) may counter that their preferred remedies achieve the same result. […] One thing is certain, however. Under fusion, the incentive is for two or more parties to agree on just one candidate. They do not compete for votes: first-choice, second-choice, or otherwise. Rather, they pool effort behind victory for the coalition. Evidence also suggests that fusion increases voter turnout, mainly by mobilizing voters who do not turn out for either major party (Michelson and Susin 2004; Kantack 2017). For more information on fusion, including its history in American elections, see a comprehensive book by Lisa Disch (2002).

At this point, some may note that no proposal deals with the Senate. Even if we can design a system for multiparty coalition within the separation of powers, the Senate still entrenches a minority veto. Further, the critical determinant of this veto — an equal number of Senators per state, regardless of population — cannot be removed from the Constitution.

My expert report only deals indirectly with the presidentialism issues above.