When seeking to persuade people to go along with an electoral reform, it is common to suggest that first-past-the-post is old. Common variations on this theme include “antiquated voting system” and “18th-century voting technology.” This trope is anachronistic.

Single-seat districts with plurality allocation and a single round in which each party nominates one candidate (i.e., FPTP) is relatively new. So is proportional representation (PR) based on party lists.

What was old in the countries these replaced is some combination of the following: multi-seat districts (including in Britain), two-round runoff elections, and virtually no party control of nominations. Some cases even had voice voting, as I learned this week. The single transferable vote (STV), which we hear is new technology, reflects the old order.

Scholars have been converging on a theory of electoral reform that runs roughly as follows: nomination control is the way to contain ‘populism,’ and this can be mixed with PR, plurality, or runoff.

This point starts to emerge from a 2010 article in Comparative Political Studies by Amel Ahmed, later expanded into a book. The point is that both PR and “single-member plurality (SMP)” — note the terminological difference from FPTP — were responses to a perceived threat of mass (socialist) mobilization in the late 19th century. Belgium turned to PR, and the United Kingdom went with SMP. Later work extends this explanation to other continental democracies. It also starts to emphasize the role of list PR in boosting control of nominations, had any existed at all. As for Britain, Ahmed documents a range of other practices (like gerrymandering) that came with SMP, all meant to contain what would become the Labour Party. Later work suggests that incumbents did not need control of nominations because it already had existed since the 1830s.

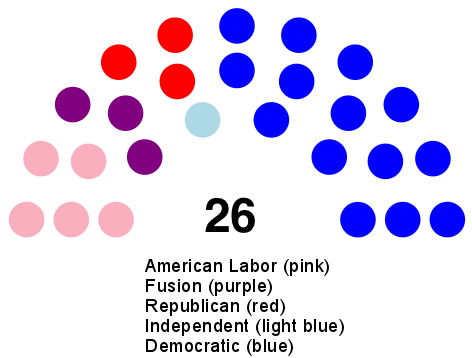

A 2×2 table may help with the jargon I am starting to introduce. It is oversimplified but helps to make my point.

| Seat allocation → Nomination control ↓ | Proportional | Not proportional |

| Low | STV | SMP* |

| High | List PR | FPTP |

How might we think about the United States? Congress first mandated single-seat districts in 1842. That law is now seen as a way to prevent Jacksonian Democrats from maximizing seat share by switching to the ‘general ticket’ (multi-seat districts) in states under their control. Note that this did not enhance control of nominations. That possibility would not exist until introduction of the secret ballot. Thus it was not FPTP, and the major parties have remained ‘big tent’ (i.e., hospitable to ‘populism’).

STV enters the conversation in the 1850s as a way to “protect minorities” in multi-seat districts, along with cumulative voting and other non-list approaches to holding down majority seat share. Its popularity is mostly limited to the United Kingdom and its colonies. I have toyed with the idea that this popularity was due to a pre-existing tradition of party government, with associated levers of nomination control. STV might have ‘protected minorities’ without resort to SMP, at the same time rolling back control of nominations. That never happened.

FPTP and list PR are thus ‘new technology,’ whereas STV and nonpartisan runoffs are old.

Since this post is getting long, I will set aside Australia, except to note three things about STV: (1) its single-seat cousin (‘RCV’) came with compulsory ranking, (2) continued mass mobilization led to the addition of compulsory voting, and (3) STV came much later to the Senate for reasons other than a need to contain ‘populism.’